9. Explicit lock

1. Lock and Reentrantlock.

ReentrantLock allows you put timeout on lock acquisition, offering greater thread liveness.

It also offers more flexible locking mechanism, where you can expand lock section across methods.

Following is the code example:

| |

You would need to lock and unlock when you enter and exit the race condition code. Users of this lock

must be wary about unlock() calls, because minor mistakes can cause code path never call unlock(),

leaving the system hanging.

1.1. Polled and timed lock acquisition.

Intrinsic locks offer no built-in mechanisms to recover from locking hazards. Once a lock ordering issue arises, the only resolution is typically a system restart.

In contrast, explicit locks provide several recovery strategies. One such method is polling with tryLock(). This allows a thread to

attempt acquiring a lock and return immediately if unsuccessful. Upon failure, the thread can then retry the acquisition or perform alternative actions like logging.

Consider the classic money transfer problem, where lock ordering can lead to deadlocks depending on the order in which accounts are given. Using the polling approach, if a deadlock occurs (indicated by a failure to acquire the final lock), the threads can back off and retry acquiring the locks after a random delay, as illustrated:

| |

1.2. Interruptible lock acquisition

Another advanced acquisition of an explicit lock is ReentrantLock.lockInterruptibly() which allows the thread waiting on lock being cancelled. You can use this

method in case it is not necessary for the thread to do further operation once it gets cancelled.

2. Performance considerations

Resources expended on lock management and scheduling can be costly which can contend the computing resources of the application. A good locking mechanism is the one:

- Makes fewer system calls: Lock mechanism when under high level of contention often resorts to system calls, especially when it needs to put the waiting thread into the waiting state. System calls are notoriously expensive due to the act of context switching, data marshaling from kernel to app memory space, cache validation and i/o flushes, ect. whereas a simple user-space operation might be nanoseconds.

- Forces fewer context switches: When a thread goes to waiting state, it lets another thread take turn to be executed, leading to thread switching. Besides, releasing lock often requires the OS to decide which threads to be awakened and run next, potentially cause context switching. Avoid context switching can significantly improve application throughput.

- Initiates less memory-synchronization traffic on the shared memory bus: As previously discussed, besides thread synchronization, locking mechanisms also ensure memory visibility between threads. This means that changes made by one thread to shared memory must be visible to other threads. This often requires the CPU executing a thread to copy its data to a shared memory bus so that other CPUs executing different threads can read it. A good locking mechanism minimizes the amount of data transferred.

- Do fewer operations that are time-consuming: Various operations locking mechanism can introduce overhead if not implemented effectively. For instances, queuing

waiting threads needs dequeue and enqueue, involving data structure manipulations that need to be synchronized themselves. Ensuring fairness locking can further

complicate this process. Also, special locking methods like

lockInterruptibly(),tryLock(time, unit)can introduce slight overhead compared to a normal locking method as they require the OS to check the interruption flag or manage timeout condition.

Intrinsic lock in Java 5.0 performs much less efficient then ReentrantLock. However, this gap is narrow down since Java 6.0.

It is worth to refer or perform a benchmark if you are in question about a lock mechanism performance.

3. Fairness

A common tendency among developers is to advocate for fairness in lock acquisition, aiming to prevent new threads from “barging in” and causing thread starvation. However, non-fair mechanisms offer their own advantages:

- They minimize thread switching.

- Often, a time gap exists between calling resume on a thread and its actual awakening. A thread that “barges in” might complete its execution before the resumed thread even starts. In such cases, everyone benefits.

Therefore, fairness typically performs best when tasks are long-running or lock acquisition times are significant.

You can enable the fairness feature in explicit locks by setting a flag to true in the ReentrantLock constructor: ReentrantLock(true).

In most common scenarios, non-fair lock acquisition is often preferable to fair acquisition. It is generally recommended to use fair mechanisms only when a specific fairness requirement exists.

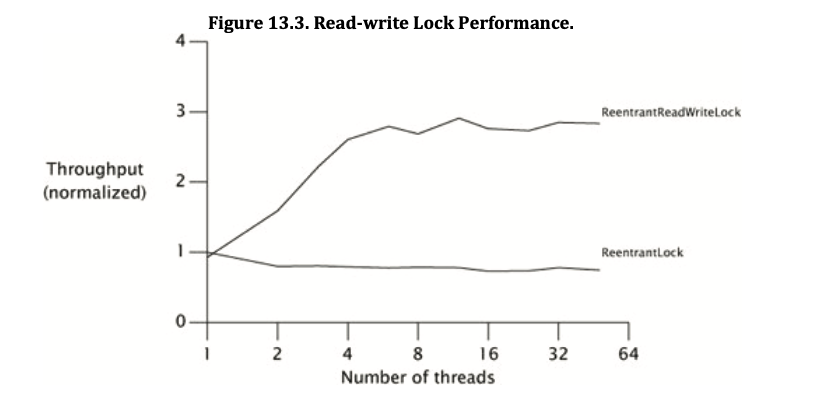

The following graph compares program throughput when wrapping fair and unfair locks around HashMap. ConcurrentHashMap, which employs a more advanced locking

mechanism called stripping lock, is also illustrated in the graph:

Intrinsic lock doesn’t offer fair lock acquisition mechanism. However, it is good enough for most situations.

4. Choosing Between Synchronized and ReentrantLock

Although most discussions in previous sections tend to favor the use of ReentrantLock, intrinsic lock is often chosen by developers

because it is safer in terms of locking management thanks to its block structured locking, thus make code more maintainable and readable.

Also, many improvements from Java community is favor synchronized over ReentrantLock too, such as lock elision for

thread‐confined lock objects and lock coarsening to eliminate synchronization with intrinsic locks (introduced in chapter 10).

Unless you need features like timed, interruptible, non-block-structured lock, or you are using Java 5.0, it is not recommended to

use ReenttrantLock just for the shake of better performance.

5. Read-write locks

When your data structure is read-intensive, another lock should be considered is ReadWriteLick

public interface ReadWriteLock {

Lock readLock();

Lock writeLock();

}

This lock operates under the principle that either multiple readers can access a resource concurrently, or a single writer has exclusive access.

As such, the performance of this lock heavily depends on the read/write ratio of your application. Therefore, it’s advisable to profile

your program to determine whether a ReadWriteLock or a traditional exclusive lock yields better performance in your specific use case.

Similar to exclusive locks, the implementation details of a ReadWriteLock can significantly impact its performance,

scheduling guarantees, acquisition preferences, fairness, and locking semantics. For instance, consider the following aspects:

- Fairness: Should preference be given to writers or readers when acquiring the lock, or should a first-come, first-served policy be enforced?

- Reentrancy: Are the read and write locks reentrant? In this context, we distinguish between two types of reentrancy:

- Downgrading: A thread holding the write lock wishes to acquire the read lock.

- Upgrading: This is the opposite of Downgrading and poses a greater challenge. When attempting to upgrade from a read lock to a write lock, the thread might need to wait for numerous existing readers to release their locks. More critically, if two readers attempt to upgrade simultaneously, a deadlock can potentially occur.

ReentrantReadWriteLock is one available implementation that allows configuration of the fairness property. Regarding reentrancy,

it supports Downgrading but explicitly disallows Upgrading.

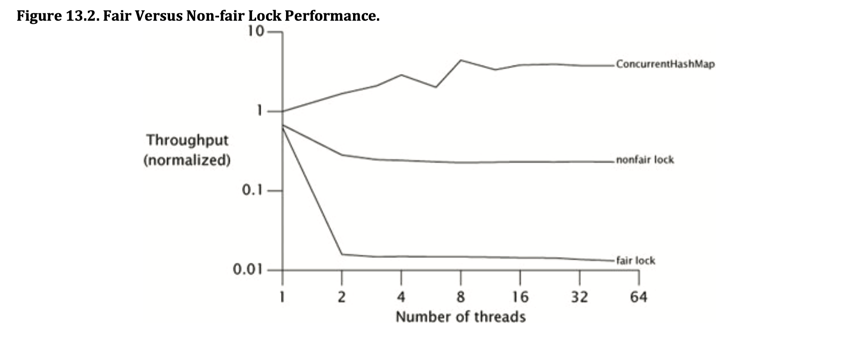

The following graph compares the performance of ReadWriteLock and ReentrantLock when used to implement a thread-safe ArrayList

in an application where read operations are significantly more frequent than write operations.